1923 and 1924 Emigrations to Canada

This story begins with the reasons the Morrison and Macaulay families decided to emigrate and why they chose Canada. Both families joined “schemes” promoted by Fr. MacDonell. The 1923 emigration of the Morrison family is described from leaving Lochboisdale; to their arrival in New Brunswick; and, to their final destination of North Battleford, Saskatchewan. The Macaulay family took a similar journey in 1924 and lived in Red Deer Alberta for two years before settling in Clandonald. Both the journeys to Canada and their first years in Canada were challenging for the settlers. Once in Canada, the families were under the care and control of the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society.

By Donald Peter Macaulay

Why Emigrate

A majority of the settlers to Clandonald were from the southern islands of the Outer Hebrides: Benbecula, Barra and South Uist. In the 1920s, the main occupations within the Hebridean economy were crofting and fishing.

Due to the lack of arable land, crofting was not easy in the barren Western Isles. the Machair land, on the western side of the islands, supported crofting, while the rugged land of the eastern side did not. That, coupled with the large size of the island families, meant there was not enough farmland to support the population. In addition, there may have been another reason for family emigration to Canada; a concern was expressed on the part of the priests and the Catholic Church, about the intermarriage of families on South Uist.

Fr. John MacMillan, a priest from Barra, accompanied the 1924 settlers to Red Deer. When the emigrants landed in St. John, he gave an interview to the Canadian press where he described the life of the crofters in South Uist, such as the Morrison family, would have led.

Small farms, averaging from ten to thirty acres, are the land areas which the Hebrides are familiar, he said. In addition, they carried on common pasture operations. Their stock consisted of from two to eight cattle and ten sheep.

In the spring the Hebridean men gathered seaweed and manured the soil with it. Then they planted oats, rye, barley and potatoes. That work done, the able-bodied men took to the sea, some engaging in fishing, others going into the merchant marine. In autumn, those who working near home, returned, reaped the crop and thatched the houses. Then they again answered the call of the sea, leaving the children and elderly people at home.

The Morrison croft house in Bualadubh, Iochdar

.png)

The Macaulay croft house in Lochcarnan

Map of the Morrison and Macaulay family croft locations in northern South Uist

The Scottish fishing industry was also in decline after the First World War. The markets for cured herring, the main island export, were depressed. Foreign trawlers, especially the Dutch, violated the three mile fishing limit and requests to the government for fishery enforcement went unheeded.

A third reason was world experience. Many islanders had fought in the First World War and had seen the deficiencies of their lifestyles compared to other parts of Britain and the continent. Angus Morrison, as an ex-soldier, would have been given preference for emigration. Some islanders had probably fought with soldiers from the Commonwealth and learned what life was like in Canada. Emigration became an opportunity to create a richer, more diverse future for themselves and their families.

Angus Morrison fought in World War I

The Morrison Family

In the 1923 SS Marloch passenger manifest, Angus and Roderick Morrison gave their occupations as farmers. Their address in the United Kingdom was Bualaduth, Cochan, South Uist. As farmers in South Uist, their main reason for emigrating was probably to find better opportunities in Canada to farm.

The Macaulay Family

Although Neil Macaulay was born in Lochcarnan, South Uist, and Mary Macaulay (MacDonald) was also born in South Uist (her family lived near Iochdar, South Uist), the couple met and were married in Glasgow in 1903. Neil Macaulay died on May 3, 1922 in Glasgow at the age of 57. Donald Macaulay, the eldest son, recalls the family being “on the dole” and having to pay part of it back once they settled in Canada.

The reason for the Macaulays to emigrate was most likely economic.

The MacPhee Family

In Donald MacPhee’s family history, Mary Theresa MacPhee writes that:

My father Donald, came over with his widowed mother from South Uist, Scotland, in 1924. After two years in the Red Deer area, they moved to the Clandonald Colony. They and my mother’s mother, brothers and sister came there at the same time, 1926.

In the book, MacPhee Clan of Alberta 1888-1983, the MacPhee emigration is described:

Mrs Kate MacPhee, a widow, left Loch Carnan, South Uist with her family of two sons, Angus John and Donald and two daughters, Mary and Christina (Chrissie) in April 1924. The eldest son, Michael, was ill and couldn’t leave with them. He was to follow later but that never materialized.

Before leaving for Canada, the family held an auction sale. The boys used some of the monies from the sale to purchase a new set of bagpipes. Both boys were good pipers and loved to play, but prior to the sale, they owned only one set of bagpipes.

Like the Macaulay family, the MacPhee family was led by a widowed mother and the reason for emigrating was economic, with the hope of a better life for their children.

Why Canada

The Hebridean emigration stories of 1923 and 1924 are a bit complicated and fraught with miscommunication, poor organisation and financial problems. A detailed account the 1923 emigration story is described by Roderick Steward in his paper, An Account of the Emigration by the People of Uists and Barra to Canada in April 1923. [Link to South Uist to Clandonald in website archive].

How Immigration to Canada Was Promoted

The 1923 emigration program was promoted and organised by Fr. Andrew MacDonell OSB, a Gaelic-speaking priest from Inverary. He had been pastor of the Catholic Church in Ladysmith on Vancouver Island in the early 1900s. In World War I, Fr. MacDonell was the Chaplin of the 67th Battalion Western Scots, Canadian Expeditionary Force. After the war, he visited the Outer Hebrides and promoted his emigration “scheme” to the islanders from the pulpit and at school meetings. Fr. MacDonell was an agent for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

As the islanders knew little about the Canadian prairies, a delegation of two laymen and two priests, led by Fr. MacDonell, toured parts of British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan in the autumn, 1922. The delegation favoured Alberta as the location for the colony. This colonisation scheme was promoted throughout the islands. In a 1925 promotional document [Hyperlink to the “1925 Promo for Hebridean Settlement in Alberta” in the Documents 1923-26 Emigrations to Canada File] for the Clandonald Colony it states:

These settlers will be carefully selected and none but good workers and experienced men need apply. None will be accepted until they are personally interviewed by Rev. Andrew MacDonell, O.S.B., M.C., Managing Director of the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society.

Roderick Steward, in his academic paper, writes that:

In 1923 the Canadian government, having taken stock of the situation in Scotland, were offering inducements to settle on Canadian soil and giving special facilities to enable immigrants to do so.

The Canadian government though entrusted a lot of the work to the whose own vested interest were reliant on the Colonization of Canada.

The Canadian Pacific Railway Company were thus an interested party in emigration as every homestead settled enhanced the value of the railways adjoining sections of land. In addition to any profit it could make by selling the land, the C.P.R. stood to benefit enormously from the increase in traffic which settlement brought.

The 100 families that created the Clandonald Colony in 1926 did not own the land but rented their farms from the Canadian Pacific Railway Company. The rent was a percentage of the farm’s annual crop yield - believed to be about one third of the harvest.

South Uist to Red Deer

Leaving South Uist in 1923

The first group of settlers destined for Canada left Lochboisdale Harbour, South Uist, on Sunday, April 16, 1923. The large group, made up of fifty families or about three hundred people, was mostly Catholic. Many of the men were ex-servicemen.

Roderick Steward again writes that:

The embarkation excited great interest throughout the islands and a large crowd gathered at the pier to watch the departure.

Before boarding their ship, the settlers were inspected by a Board of Trade Medical Officer and asked to fill out forms by the Canadian Pacific Steamship company officials in a shed on the Lochboisdale pier. After inspection only one man was rejected. Because of its size, the SS Marloch anchored off the coast and the families were ferried out to the ocean liner by a small, local trading vessel, the Durara Castle.

The Morrison Family Crossing in 1923

In the 1921 Census for South Uist, [link to Morrison, Angus Family South Uist 1921 Census] Angus Morrison’s occupation is listed as “Crofter” and Roderick Morrison’s occupation is “Croft Worker”. When filling out the Canadian Pacific Steamship Line passenger manifest [link to Marloch 1923 passenger manifest in website archive], Angus Morrison, 50 years old, gave his occupation as farmer. Mary Morrison, 40 years old, was a housewife. Roderick, 16, was a farmer and Catherine (Katie), 15, was a domestic. Peggy, 13 years old, Neil, 11, Marian, 9, and, Dougald (Donald), 6; all had “school” as their occupation. Michael, 3 years old, and Flora, 1 1/2, had “Nil” for their occupation. The entire family was travelling 3rd class.

Peggy Morrison also filled out a separate Declaration of Passenger to Canada form [Link to Peggy Morrison 1923 passenger declaration form in the website archive]. On it she described herself as single female with an occupation of scholar. Her Race or People was “Scots”, her Citizenship, “British”, and her religion, “Catholic”. Her object in going to Canada was “to settle” and when asked if she intended to remain permanently in Canada she said “Yes”.

When asked how much money she had in her possession, Peggy replied “3 pounds”. She said she could read and the language was “English”. When asked who paid her passage, Peggy replied “Can. Govt”. She confirmed that she had never been refused entry to Canada or been deported from Canada. Her destination in Canada was to be “Rev. A. MacDonell, Red Deer Alta.” Her nearest relative in the country she came from was: “Neil MacPhee, Grandfather, Gerinish, South Uist”.

On the form, Peggy replied “No” to:

-

Are you or any of your family mentally defective?

-

Tubercular?

-

Physically defective?

-

Otherwise debarred under Canadian Immigration Law?

The signature of the passenger was “Peggy Morrison” and the final signature was the Booking Agent, confirming all the preceding information.

Morag Bennett, in her oral history, recalls the 1923 crossing of the Marloch:

Oh I remember quite a bit about the voyage; the ice bergs and it was foggy; and, we had to anchor and it took us, oh my goodness, about two weeks to cross. We were stuck in the fog and the ice bergs were huge. I remember the blasting of the fog horn for sure. I can still hear it. And of course we were put in the state rooms to sleep and, you know, we never had running water in Benbecula, there was just a well. And we didn’t know what the bowl and the taps and certain things were for, you know.

Alex Norman MacPhee, in the book, MacPhee Clan of Alberta 1888-1983, remembers other adventures:

Alex tells that, on the trip over from South Uist, he remembers being thrown off the top bunk and across the cabin to land under the lower bunk opposite him, because of the boat in the heavy seas.

New Brunswick to Alberta and Saskatchewan

The Marloch docked at St. John, New Brunswick, and the settlers were put on two trains, possibly because more families arrived than were expected. On arrival of the trains in Winnipeg, Fr. MacDonell gave them the bad news.

There had been a misunderstanding between the arrangements Fr. MacDonell had made with the delegation that toured the prairies in the autumn of 1922 and what actually took place in 1923. The “deal” according to Father MacDonell was:

It was agreed that a party of 18 families would be enough to begin settlement and that each family should have $1,000 or at least $750 capital to purchase a farm and to provide certain equipment.

In the book, MacPhee Clan of Alberta 1888-1983, the situation at St. John was described as:

In the end, 50 families, 300 people, arrived at St. Johns, New Brunswick, half with no money, as they had sold all their possessions and used the proceeds to purchase their passages on the boat. Here they were met at the docks by Father MacDonell. He states:

While standing on the docks at St. Johns watching the ship being tied up, I was given two telegrams, one from Mr. Blair again urging me to divide up the families and the second from the Minister of Alberta, “Regret this government unable to settle any of your families.” (Mr. Blair was from the Colonisation Department at Ottawa.)

Following the government demand that the 50 families be divided up, 20 families with no money were sent to settlements in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. The Morrison family was one of the families that did not go to Red Deer, but instead went to Saskatchewan. Of the 30 families that travelled from St. John to Red Deer, Alex Norman MacPhee, in the book, MacPhee Clan of Alberta 1888-1983, remembers the train trip as follows:

Add to this the long train ride sitting on straight back benches, the stopovers during which passengers provided meals for themselves over open fires or any way they could arrange; and their exhaustion upon arrival becomes apparent.

The Morrison Family in North Battleford 1923 to 1926

The Morrisons were sent to a farm in North Battleford, Saskatchewan in late April, 1923. Little is know of the type and location of their farm outside North Battleford. The family patriarch, Angus Morrison, died soon after arriving in Canada on September 11, 1923, and is buried in North Battleford.

%20Morrison%2C%20Margaret%20(Peggy)%20Morrison%2C%20Mary%20Morrison%3B%20front.jpg)

Back Row L-R: Jim MacDonald, a family friend, Catherine (Katie) Morrison, Margaret (Peggy) Morrison, Mary Morrison; Front Row: Michael Morrison, Flora Morrison; North Battleford, Saskatchewan, 1923

Katie Morrison, Mary Morrison, family friend, Marion Morrison in North Battleford, 1924/25

In preparation for the 1983 Morrison/Macaulay family reunion, Katie Macaulay told some stories of her family’s time in North Battleford to her niece, Mary Baxter. Katie and her sister, Peggy, had good jobs and the Morrisons were well established on their farm. The prairie surrounding North Battleford was flat and that part of Saskatchewan provided better town and farming opportunities than Clandonald.

Even in 1983, Katie was still angry and felt it was unfair, that a priest, possibly associated with the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society, forced her family to leave North Battleford to join the Clandonald Colony. The reason given by the priest for this move, was that the Morrisons, who had been farming in Saskatchewan since 1923, could help the new arrivals settle in Clandonald.

Tragedy again struck the Morrison family in 1925. The eldest son, Roderick, had an accident [link to Roderick Morrison funeral notice] which left him with permanent brain damage. Roderick was sent back to Scotland to the Craig Dunain Hospital, a mental health facility near Inverness in Scotland. He spent the remaining 57 years of his life in the hospital. After he died, Mike Morrison arranged to have Roderick’s remains taken back to South Uist and he was buried in the graveyard at Ardivachar.

Back Row L-R Neil Morrison, Marion Morrison, Mary Morrison, Margaret (Peggy) Morrison; Front Row: Mike Morrison, Donald Morrison, Flora Morrison; North Battleford, Saskatchewan, 1925

1923 Settlers in Red Deer

When the settlers arrived in Red Deer, they were welcomed by the Saint Andrews Society with pipes and speeches. Fr. MacDonell stated: “We came to Canada to make Canada better and to make ourselves better.” An article in the March 2, 2016 edition of the Red Deer Express describes in more detail the arrival of the 30 families in Red Deer:

There was considerable excitement in the community with the first groups of Hebrideans arrived in Red Deer on May 8, 1923. The first train came in the C.P.R. station in the morning and then another at the C.N.R. station in the afternoon.

An estimated 2,000 people turned out for the welcoming ceremonies, not far short of the entire population of the City. The dignitaries present made lofty speeches - referring to the Hebrideans as a, “Class of people that keep their Sabbath” and as “loyal subjects” of the British Empire.

There was the realisation that most of the newcomers did not speak English. Consequently, a number of local residents were recruited to speak Gaelic to the Hebrideans upon their arrival.

Over the next few weeks, the Hebrideans, who had largely been fishermen, were trained in farming and English. Father John McMillan, another Catholic priest, was assigned to help with the resettlement.

As each settler and family were deemed ready, they were sent out to farms west of Red Deer, or in the Westlock and Vermilion areas.

However, this first Hibridean group did stir up some controversy as detailed in the Red Deer Express article:

However, before long grumblings began to emerge. Rumours began to circulate that the Hebrideans were given special favours, such as exemption from taxation, and grants, not loans. Others claimed the Soldiers Settlement Board was displacing veterans to secure farms for the new settlers.

In a 1923 report that Fr. MacDonell prepared on the “Expenses incurred in re Hebridean Settlement” he outlines some of the reasons for the lack of money for half of this first group and how he tried to deal with those problems.

The money troubles for the first group of immigrants started on the islands. Once perspective immigrants heard that there was to “a nominated Passage Scheme” to go to Canada, they rushed to sell their stock (cows, sheep and horses) and chattels before their neighbours, in the fall of 1922. By the time they could leave in April, 1923, “many had already made very serious inroads upon their little capital.”

When they arrived in Red Deer in May, many had no money and large families to feed. Fr. MacDonell made arrangements to feed them while trying to get them placed on farms as quickly as possible. While staying in Red Deer, the settlers learned Canadian farming methods - “harnessing horses, four horse hitch, plowing with gang plow, etc.”

Note 1

To his credit Fr. MacDonnell was able to place most of this first group of settlers on farms within two months of the settlers reaching Red Deer as described in newspapers at the time. [link to 1923 Edmonton newspaper article in website archive]

Creation of the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society

Learning from a number of problems encountered in the 1923 Hebridean emigration, Fr. MacDonell formed the Scottish Immigration Aid Society. The society was incorporated under the laws of the Dominion of Canada on a non-profit, sharing basis and its aim was to assist emigration to Canada from Great Britain and Ireland. The board of the society, all millionaires, included: General Stewart of Vancouver, President; Colonel J.S. Dennis, Chief Commissioner of Colonization, C.P.R.; and, Father MacDonell, Managing Director.

The society was able to negotiate contracts and agreements with the Overseas Settlement Department of Great Britain; the Canadian Pacific Railway Colonization Department; the government of Alberta; and, the Canadian Department of Immigration and Colonization.

The Red Deer Industrial Institute

The Missionary Society of the Methodist Church operated the Red Deer Industrial Institute as a First Nations residential school from 1893 to 1919. The school was built by the Department of Indian Affairs on 480 acres of land on the west bank of the Red Deer River. The mandate of the Institute was to train its students in certain trades such as carpentry, blacksmithing and farming.

Red Deer Industrial Institute, 1900

After the First World War, the school buildings were used as an agricultural training centre by the Soldier’s Settlement Board for returning veterans. The school buildings and farm were vacant in 1923.

In March 8, 1923, the Department of Immigration and Colonization leased the Red Deer Industrial Institute farm and buildings to the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society for a period of five years at the cost of $1 per year. The department also gave the society a grant of $5,500 to repair the buildings on the farm and install a lighting system. The Canadian government also made an annual grant of $5,000 to the society to promote immigration and colonization from 1924 to the end of 1927 for a grant total of $20,000.

The purpose of the grants was to help and care for the settlers the Society was bringing from Scotland and Great Britain so that they will be able “to settle securely and permanently in Alberta”. The farm and buildings were to be used as a central headquarters for the Society.

Ard-Moire 1923

Father MacDonell gave the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society headquarters at Red Deer the Gaelic name of “Ard-Moire”. The Society’s plan for the site was to use the buildings and farm as a receiving, training and distribution centre for the Hebridean immigrants. The 1923 Hebridean immigrants were housed in the dormitory building until farms could be found for them through the Soldier’s Settlement Board (S.S.B.). As these large families had little money, the SIAS found money to feed them for the time they were in Red Deer. Approximately 100 children contracted measles in Winnipeg on the way to Red Deer and they were cared for by a doctor and nurses in the dormitory building.

In the 1923 facility report on Ard-Moire, Father MacDonell relates how the farm was used as a training facility:

The farm proved very valuable from a training standpoint. An officer of the S.S.B. was made available and 60 men and boys were made acquainted with the elements of Canadian farming methods: the harnessing of horses, the use of wagon, and driving of teams, ploughing with gang plow, breaking and seeding, etc.

Ard-Moire was also used for training the 1924 immigrants who spent two years at the farm before moving to Clandonald

Note 2

Stables and barns at Ard-Moire used to house the cows and horses used in farm training.

In the 1923 facilities report, Fr. MacDonnell also laid out his plans to send Fr. John MacMillan, who was stationed at Red Deer and an excellent Gaelic speaker, to the Hebrides for three months to explain how the 1923 settlers were successfully settled in Canada. As part of this promotional work, Fr. Father MacDonnell also planned to go the Hebrides and mainland Scotland in order to recruit a “much larger body of settlers from the Highlands of Scotland this coming year.”

Note 3

The Canadian press had articles on the success of the 1923 emigration to Alberta. An excerpt from a larger article that appeared in the November 3, 1923 edition of The Toronto Star Weekly follows.

The Toronto Star Weekly Article

Cottages Built At Ard-Moire

One of the biggest problems identified in 1923, with the process of integrating the Hebridean settlers into Alberta, was the provision of suitable accommodation for large families on local farms, while the men and boys learned Canadian farming methods by acting as farm workers.

To deal with that problem, the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society contracted the Carter-Halls-Aldinger Company of Edmonton to build eighteen cottages, six at Ard-Moire, six at St. Albert, two near Wetaskwin, two near Lacombe and two near Camrose. The six cottages for Ard-Moire were to be built on three acre plots near the farm so the settlers could grow vegetables and grain crops for their families.

The cottages were to be built and ready for the next group of settlers by April, 1924.

Stretching the Truth

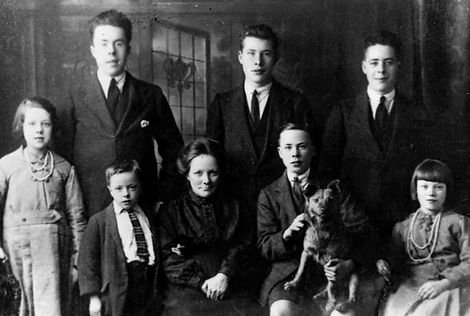

The Macaulay Family 1922; Back Row L-R: Donald Macaulay, Angus Macaulay, Peter Macaulay; Front Row L-R: Catherine Macaulay, Neil (Nelie) Macaulay, Mary (Wee Granny) Macaulay, John Angus (Jock) Macaulay, Marion (Morag) Macaulay

Just as with the 1923 Marloch voyage, the Macaulay family was listed on the Canadian Pacific Steamship Line passenger manifest for the liner Marlock, leaving from Glasgow [link to Marloch 1924 passenger manifest for Glasgow in website archive]. Mary Macaulay, aged 49 years, gave her occupation as housewife. Donald, aged 19 years, Angus, aged 18, and, John A., aged 15, all gave their occupation as farm workers. Catherine, aged 12 years, Marion, aged 11, and Neil, aged 9, had school as their occupation.

Donald Macaulay, in a letter to Sister Patricia Macaulay in 1963, [link to Sister Pat letter in website archive], declared that the Macaulay family, except for Peter, boarded the Marloch in Glasgow where the ocean liner started its trip to Canada. Peter had taken his mother’s father, Angus MacDonald, to South Uist a few days earlier and planned to join the ship in Lochboisdale. Donald recounted that there was some drama on the Lochboisdale pier with his mother making quite a scene by shouting in Gaelic and English: “Where is my Peter!” Wee Granny must have come off the Marloch when it anchored off Lochboisdale, and taken the tender, which was ferrying passengers to the liner, back to the pier to look for her son.

Peter is listed on the 1924 passenger manifesto for Lochboisdale [Link to Marloch 1924 passenger manifest for Lochboisdale in website archive] and gave his age as 16 and his occupation as “crofter”. He also stated his last address on leaving the United Kingdom as Clachan, Iochdar, South Uist, the croft which belonged to his grandfather, Angus MacDonald, the person he accompanied back to South Uist.

In the 1921 census for Glasgow, [Link to Macaulay, Neil Family Glasgow 1921 Census in website archive] Neil Macaulay’s occupation is as an Assistant Janitor working for the Board of Trade Shipping Office; Donald is an Engineer working for J. Howden Co., Engineers; Angus is a Clock Repairer working for Stromer Co. Watchmaker; and, Peter and John Angus are messenger boys. The remaining children are “Scholars”.

In his letter to Sister Patricia, Donald Macaulay describes himself as being “blacker than the ace of spades” after a stint working as an engineer servicing machinery in a factory. After his father died, Peter took up a job as a counter man in a pub, owned by a cousin of his father. The pub was located in Wishaw, a small town 30 miles south of Glasgow.

There are Macaulay family stories of the older sons spending their summers on South Uist working on the crofts of relatives. Angus Macaulay worked on the croft belonging to his mother’s parents, Angus and Catherine MacDonald.

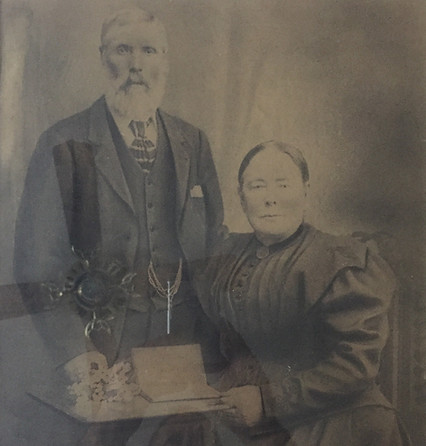

Angus and Catherine MacDonald, Mary Macaulay’s parents

Perhaps it is this “croft experience”, that Donald, Angus, Peter and John Angus were thinking of, when they said their occupations were farm workers or crofters. That would have been necessary to qualify for the 1924 emigration program sponsored by the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society. All the potential candidates for the crossing were interviewed and preference was given to those that had farm experience.

The Macaulay Family Crossing in 1924

There was sad start to the journey to Canada for the Kate MacPhee family who left with the Macaulays. There were a number of Scottish newspaper reporters on the pier at Lochboisdale and one recorded what happened to the MacPhee family.

There was only one case of actual rejection on the Lochboisdale pier. A young fellow, MacPhee, was found to be suffering from some trouble in his ear, and the doctor would not let him go. He was going out with his widowed mother and his two brothers and two sisters. The croft had been sold, and for some agonising minutes the family could not decide what to do. They were for remaining in the South Uist. But where would they stay? The authorities, however, with great kindness and tact, managed to point out that the boy could be taken to Glasgow infirmary and his ear put right, and that he could follow in a later boat. So the family left without him. But young MacPhee would not remain in the Uist. There and then he got a passage in a boat going to the mainland.

Michael MacPhee, the eldest son, never did go to Canada. The newspaper reporters also reported on the lighter side of events on the pier in Lochboisdale as the settlers were loaded onto the West Highland steamer, Hebrides, to be taken out to the Marloch.

The Hectic Hebrides

There is a famous photo of Donald Macaulay piping on the Marloch as it left South Uist, which was featured in a number of Scottish newspapers at the time. In the front row of the folks watching Donald play, is his young sister, Marion, identified by her dark hair cut in a “fringed bob” and her proud smile.

In the section on the Kate MacPhee family in the MacPhee Clan of Alberta 1888-1983, there is a detailed story of the 1924 journey of the Hebrideans from Scotland to Alberta. This is an edited version of that story by one of Kate’s daughter:

The first night out, the ship ran into a fierce Atlantic gale. The ship was rolling in the rough seas and suitcases were thrown from side to side in the cabin. At times the waves washed over the ship and water covered the cabin floor. The storm was so violent that the ship engines had to be turned off and the ship drifted with the storm. By the time the storm had abated, they were 60 nautical miles off course and everyone but young Alick was seasick.

After that bad night, it was fairly smooth sailing. The ship returned to its proper course the next day. There were fifty families from South Uist, Benbecula and Barra on board and most of the men could play the bagpipes, so pipe music could be heard from morning until night.

Note 4

Hebridean women on the Marloch; Kate MacPhee is in the back row holding one of her daughters and Mary Macaulay (Wee Granny) is third from the left in the front row

Neil Macaulay’s recollections of the crossing were:

It was a very rough trip so most of the people got seasick. Donald, who was to be a sailor, was the worst in our family. In later years he told us that, when he was on shore leave, he would be still be sick. So you can image what a hard life it was for him.

The 1924 ocean journey of the Marloch received considerable coverage in the Canadian press. After leaving Lochboisdale liner stopped in Stornoway, on Lewis and Harris, to pick up more settlers. One article described in detail the crossing and life on board the liner.

The Marloch left the Hebrides on April 14, and for three days the vessel travelled at the usual rate of speed. Then she was enveloped in a blanket of fog so thick that, according to passengers, the surface of the water was not visible, while officers of the ship said the masts were not visible from the bridge. For four days, it was said by a passenger, the Marloch merely drifted, one day going about eight miles, another day 10, another day 22 and another day 42.

A total of 37 icebergs were reported to have been seen, eight of which were passed in one day. The sirens of other ships, also blanketed were heard.

Concerts, whist parties, dances and movie entertainments enlivened the passage. There were many talented signers, dancers and instrumentalists among the Hebridians, and they greatly aided in making the voyage merry. The cabin passengers had two concerts and the third class three; each class had dances and two movie concerts.

The arrival of the Marloch on April 29, 1924, at St. John, New Brunswick was colourfully described by the Canadian Press.

To the merry skirl of the pipes, the Hebridians who left their native land on the steamer Marloch to seek their fortunes in the New World, stepped briskly down the gangway this morning and marched from the deck to the immigration sheds. There they were formally welcomed to Canada by Mayor Fisher of John.

The large group of Scots who came to St. John today, the first group of Britishers to come here in years as a body, was most favourably commented on by the local people who watched the debarking. Alert, rugged, self-reliant, and showing in a pronounced degree of color which comes of good health, the Hebridians impressed onlookers as just the right type, physically and mentally, to make good in this country.

St. Andrew’s Society was represented in force among the welcoming party, and their piper was present in Highland costume and playing during the landing, during the march to the immigration building and during the routine examination by the Government officials. Pipers among the Hebridians also furnished music in the immigration building.

The Hebridians are in charge of Rev. John MacMillan who will remain with them at Red Deer, their destination, as pastor. Rev. Alexander J. Gillies, who will remain with the party until they are finally settled, will return to the Hebrides. They were welcomed at the pier by Rev. Andrew MacDonnell, formerly of Invergarry, Scotland, who is now located in Ontario, and who has arranged for and brought here several parties from the Old Land.

Note 5

New Brunswick to Red Deer in 1924

In the MacPhee Clan of Alberta 1888-1983, Kate MacPhees daughter describes the journey to Red Deer:

After five days and nights of cramped train travel, my grandmother and her family arrived in Red Deer, Alberta. They were transported by cars to a vacant Indian residential school. In addition to the school, several small cottages were used to house immigrants. My grandmother and her family lived in one of these cottages.

Angus Macaulay remembered the train ride across Canada. He said that he and his brothers were given a bit of a rough time by the other young men on the train because of their accents and funny clothes, as they wore wool, not denim.

The 1924 group of settlers did not get the same welcome the ones in 1923 received. There were no speeches or a pipe band. The Board of Trade, however, did provide rides out to the residential school and farm. Like the MacPhees, the Macaulays were given one of the cottages at Ard-Moire when they arrived.

Ard-Moire 1924 to 1926

The facilities at Ard-Moire were in much better shape for the 1924 immigrants. The old residential school buildings had been repaired and made ready for training in Canadian farming techniques. Teams of horses and cows had be acquired to aid in the training. Six cottages had been constructed on three acres plots in the spring of 1924. The families in the cottages were encouraged to plant vegetable gardens and grain fields for their own use.

A room in the residential school was provided for the 20-30 younger children who arrived in 1924. Neil Macaulay had memories of that time:

We got on a train and started on the long trip out to Red Deer Alberta where Father MacDonell had a row of cottages built to receive most of us. Others stayed at what used to be an Indian school. He also brought out a school teacher, Morag Morrison. She was able to get a room in the Indian building to make a classroom. Marion and myself went to it.

Note 6

Two Frame Cottages at Ard-Moira

Neil also recounted stories of his experiences at Ard-Moira:

Something that may be of interest to you the reader is the fact that while staying in the “cottages” we experienced the worst hailstorm Red Deer had in many years. It lasted about one half hour. After it was over we went outside and picked up some hailstones. They were as big as eggs. They broke the windows on one side of the cottage we were staying in. At the back of the cottage there was a field of rye standing four feet high. After the hailstorm you could not pick up a piece of straw more than a few inches long!

While staying at the cottages, the older boys went to work for farmers in the Lacombe area in Alberta. The idea was for them to learn farming. They would come home on weekends and join in on all the visiting at the cottages.

In a July, 1925 letter to the Mr. Egan, Deputy Minister in the Department of Immigration, Father MacDonnell reported on how many settlers the Scottish Immigrant Aid Society brought into Canada between 1921 and 1925. His total amounted to 1,325 individuals. Many of the settlers who arrived in 1924 and 1925 were still waiting to be placed on farms. They were, however, working for Alberta farmers, gaining experience and learning about the conditions of farming in Canada.

One of the “conditions” learned about Canada was how cold a prairie winter could be. Fr. MacDonell reported that:

The abnormally hard winter of 1924-25 was very severe on most of the settlers. There were several casualties. The most serious was the case of Thomas Gillies, a hard working excellent farmer. His feet were frozen while in the bush. He has lost his toes and part of his foot and will be incapable of further farming. I making every effort to get him suitable work. He has a wife and 7 children. The Society has been keeping the family since the New Year.

The Society had to keep several families in food, and to provide clothing and boots and moccasins for several other families during the exceptional winter. Farmers who had intended to keep men, let them go because the winter was so severe, and they feared it would not pay to keep men. Several such cases occurred. In this we have sufficient reason why certain members of the August party, 1924 got discouraged and asked to be sent home.

Note 7

The older Macaulays, Donald, Angus, Peter and John Angus would have worked for local farmers during the harvest of 1924. With unseasonable cold winter that year, working on local farms was impossible.

Note 1: The “1923 Fr. MacDonell Report” can be found in the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection (Correspondence, 1912-1923; pages 103 -104) ; the Rare Books and Special Collections, University of British Columbia Library.

Note 2: This photo can be found in the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection (CCPH-01676) ; the Rare Books and Special Collections, University of British Columbia Library.

Note 3: The “1923 Ard-Moire Facilities Report” can be found in the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection (Correspondence, 1924; pages 1-4) ; the Rare Books and Special Collections, University of British Columbia Library.

Note 4: This photo can be found in the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection (CCPH-01595); the Rare Books and Special Collections, University of British Columbia Library.

Note 5: The previous mentioned newspaper articles from Scotland and Canada can be found in the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection (Clippings book of newspaper articles written by MacDonell or relating to Clandonald; pages 49-69) ; the Rare Books and Special Collections, University of British Columbia Library.

Note 6: This photo can be found in the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection (CCPH-01677) ; the Rare Books and Special Collections, University of British Columbia Library.

Note 7: “Fr. MacDonell’s 1925 letter” can be found in the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection (Correspondence, 1925; pages 59-60) ; the Rare Books and Special Collections, University of British Columbia Library.

Resources:

MacPhee, Babara Redd and MacPhee, Betty Bretton. MacPhee Clan of Alberta 1888-1983. Self-published, 1884.

Steward, Roderick. An Account of the Emigration by the People of Uists and Barra to Canada in April 1923. Notre Dame College of Education, Glasgow, Scotland. History Dissertation, April, 1980.